MR. ZUSS: God never laughs! In the whole Bible!

— J. B.

MacLeish’s Zuss is patently wrong. The Hebrew scriptures record the laughter of God no fewer than seven times on at least six occasions.Consistently it is indignant laughter (“laughed them to scorn”) at those who are evil — at Sennacherib of Assyria (2 Kings 19:21; Isaiah 37:22), at unrepentant sinners (Proverbs 1: 26), at those plotting against the just (Psalms 37:13), or at the vain kings of the earth (Psalm 2:4). Admittedly, the spectacle of the Almighty laughing at lesser creations hardly strikes some of us mortals as comic. Like Job, we cynically see ourselves as righteous victims of a supernatural joke, believing that God “mocks at the calamity of the innocent” (Job 9:23).Yet in the divine comedy it is our own posturing of innocence and righteousness that is ludicrous.

Zuss’s error is but a symptom of a widespread theological aberration: he misconceives God as a humorless taskmaster out of touch with the wells of good nature and animal spirits. It is perverse to receive the Gospel as bad news, as a revelation of man’s evil rather than a celebration of God’s good. Those who search to support this misconception have little trouble finding support, particularly in the Hebrew scriptures.” Even in laughter the heart is sad, and the end of joy is grief” (Proverbs 14:13). “I said of laughter, ‘It is mad,’ and of pleasure, ‘What use is it?'” (Ecclesiastes 2:2). “Sorrow is better than laughter, for by sadness of countenance the heart is made glad.” (Ecclesiastes 7:3). In the Christian scriptures they have to dig harder, but anyone can find a sad-faced Jesus if the mind is set to do so. After all, every schoolboy knows the shortest verse of the Bible; and with it, the hard of heart, as if by some form of hocus pocus, can nullify or diminish Jesus’ overarching mission of grace, joy and redemption.

Some modern Christians have trouble hearing the laughter of Jesus because the religious Establishment frequently portrays Jesus in the service of stern authoritarianism. An authoritarian Jesus constrasts starkly and ironically with the Jesus of scriputure. In the bible Jesus treats authoritarians as enemies. Legalist Christians today are out of touch with Jesus the boisterous rule-breaker. Jesus storms the temple (John 2:13-17), turning over the tables of the money-changers. We are meant to delight in the sound of the money “poured out” and in the sound ofthe “whip of chords” Jesus used to drive the vendors away.

To enjoy the Jesus of scripture, we need to appreciate sarcasm, puns, enigmas and paradoxes — all part of Jesus’ arsenal, coming as he did from the doubly persecuted minority of Jew an independent prophet. Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews, visited Jesus, “by night,” as if to avoid embarrassment. Jesus embarrassed another prominent person by indulging a vagrant prostitute and allowing her to bathe his feet with precious oils bought with her earnings. From a Third World point of view, such scenes are richly humorous, full of high spirits, acceptance, and welcome. They show Jesus as warm, personal, and sensual.

When the Establishment criticized Jesus for breaking the Sabbath rules, he affirmed that rules should serve people, not people the rules. Note the muffled laughter implicit when Jesus answers his accusers, especially as he cuts through their intellectual pretension to know all scripture: “Have you not read what David did, when he was hungry?” (Matthew 12:3). Jesus jokes about the rich:”It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew 19:23). If we identify with the rich man, the remark is splenetic. Yet the original audience were mainly poor, and they had just witnessed a young man with “great possessions” exposed for not really being so perfect as he wanted to think himself. The poor in every age are used to the rich who withdraw when they realize that to gain life they will have to lose it.

Jesus is the original jive artists, the crafty maker of small talk to keep those in power structure at bay. Even when brought in as a prophet on display at the homes of the powerful, he does not cut himself off from his kind of people, the poor. He talks to both groups at once. At times this rhetorical gymnastic renders symptoms of paranoia .Paranoia is sometimes the healthy response of a rebel who is in the presence of real enemies. Jesus’ humor becomes private, in-group, especially when he is aware that spies are trying to trick him:

“Is it lawful for us to give tribute to Caesar, or not?” But he perceived their craftiness, and said to them, “Show me a coin.Whose likeness and inscription has it?” They said, “Caesar’s.” He said to them, “Then render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they were not able in the presence of the people to catch him by what he said, but marveling at his answer they were silent.” (Luke 20:22-26)

Jesus’ answer is really a non-answer: the new terms are ambiguous. He has not really identified “the things that are Caesar’s.” The spies (and we) still have no way of knowing whether tribute to Caesar is right or wrong. If they think that it is right to pay taxes, that is only their interpretation. Although for centuries preachers have used this episode to justify the Church’s historical deference to the State, the passage remains equivocal. Jesus has possibly referred only to this one coin. We, like his original hearers, cannot be sure. Such are the games jive artists play when they are threatened. One thing we can be sure of, however: Jesus has confounded his enemies. “And they were not able in the presence of the people to catch him by what he said.” He has won a respite by the wit of obfuscation. Those who have watched Mister Charlie try to get unequivocal answers out of debtor Blacks talking on stoops in the ghetto are familiar with skillful equivocation as an important verbal ruse of the oppressed.

Jesus times some of his most startling theological insights to detonate after a delay. Witness the episode when the Sadducees tried to trip up Jesus in a tedious argument about the resurrection, in which they did not believe (Matthew 22). Jesus goes along with the terms of the question initially: “You are wrong because you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God” (verse 29). Yet his follow-up is fresh theological matter not in the Hebrew scriptures: “For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven” (verse 30). While the Sadducees sweat out their failing memories to discover the allusion, which is really a smoke-screen, Jesus shifts ground, seeming to leave the terms of the question altogether: “And as for the resurrection of the dead, have you not read what was said to you by God, ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’? ” (verses 31 and 32). Jesus seems to digress. What have Abraham, Jacob and Isaac to do with the resurrection? Then comes the punch line: “God is not God of the dead, but of the living” (verse 32). Quibbling about the resurrection (future) or the past misses the essence of religious revelation, namely, God reveals God’s self always in the now. Jesus uses a verbal trap to expose the verbal trap of his enemies, uses a reference to a Biblical rhetorical mode to reveal God’s means of relation to all people in any time. The wit and the dodginessis incisive and subtly comic.

Jesus does not take just occasional pot shots: insider-humor is part of the comprehensive strategy of the parables:

Then the disciples came and said to him, “Why do you speak to them in parables?”And he answered them, “To you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given … This is why I speak to them in parables, because seeing they do not see, and hearing they do not hear, nor do they understand.” (Matthew 13:10-11, 13)

Jesus’ verbal pyrotechniques are of many sorts .He relishes farce, as in his extended metaphor: “Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but you do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, “Let me take the speck out of your eye,” when there is the log in your own eye?” (Matthew 7:3-5. He wields sarcasm, as in “And when you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces that their fasting may be seen by others. Truly, I say to you, they have their reward” (Matthew 6:16). His final slice suggests that the only reward they will get is their current reputation, that they pray not to God but for the observers. Obscured in the English version is the added humor of the pun on “disfigure” in the Greek, “disfiguring” oneself to make a “figure” or grand appearance.

Jesus exploits hyperbole and name-calling, as in “You blind guides, straining out a gnat and swallowing a camel!”(Matthew 23:24) and in “you are like whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within they are full of dead men’s bones and all uncleanness”(Matthew 23:27). This color contrast appeals to darker Semitic folks; Pharisaic cleanliness takes on a vicious reassociation, from ‘white as pure’ to

‘white a ghostly, deadly.’

Jesus is good company among friends as well, as was vividly brought home to me in a Greek class in the 1950s when a fellow student, a puritanical preacher, struggled to translate the story of the first miracle, that great practical joke Jesus pulled by making super-strong wine from water at the wedding feast in Cana (John 2).

“Water to grape juice,”offered the student, eyeing the professor. There was silence.All stared at an RSV crib of verse 10, in which the ruler of the feast complains: “Everyone serves the good wine first; and when they people have drunk freely, then the poor wine; but you have kept the good wine until now.”

“Does grape juice get rated ‘good’ and ‘poor’?” the professor teased. “Is not this word oinos (‘wine’) the same Xenophon uses when noting how the men of Cyrus get delayed every time they overindulge?”

“B, B, But …” the student stuttered.

“I think I get your point,” the professor interrupted. “You would like to think that the God of the universe would not spike the punch.”

“Right!” the student replied.

“There is only one thing wrong with your position,” the professor said, “namely you are putting yourself in a position to tell God what God can and cannot do.”

Somber expectations of holy writ take much way from the good fun in the Gospels. Read with dullness, the story of the calming of the storm is frightening: “‘Save, Lord; we are perishing.’ And he said to them, ‘Why are you afraid, you of little faith?'” (Matthew 8:25-26). An authoritarian sees this text much as one might view a parent coming to the bedroom to rebuke a frightened child for his belief in goblins. But the authoritarian fails to see another kind of parent, one who is not annoyed

but lovingly blows away the goblins, acting out the child’s need for a hero, respecting the childness of the child. The text says that Jesus “rebuked the winds and the sea,” not the disciples.

Even on solemn occasions, Jesus jests. He institutes the Church with a pun: “And I tell you, you are Peter [Greek Petros] and on this rock [Greek petra] I will build my Church” (Matthew 16:18). Note the inuendo that many intend when they nickname a friend “Rock” or “Rockie.” Similarly, when Jesus calls fishermen as disciples he does so with word play: “I will make you become fishers of men” (Mark 1:17). Before revealing to the woman at the well the place where really God dwells, Jesus teases her. He knows all about her promiscuity, but he provokes her to talk about herself openly, warmly.

Fine mixtures of humor and seriousness are integral to the Good News.

At the heart of Jesus’ humor is paradox. Nowhere is paradox more explicit than in the Beatitudes (Matthew 5), which celebrate a happiness (blessedness) begot of poverty of spirit, mourning, meekness, etc. Happiness in a sick society is enjoyed not by espousing the values of that society, but by countering those values and moving into a new, strange dimension. Our culture does not educate us to see the humor, even the laughter in paradox. A Zen master would understand. Perhaps the greatest laugh of all is the confident, joyful laugh in the face of adversity.

The resurrection presents sublimist laughter, laughter at death itself. As St. Paul interpreted it: “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” (I Corinthians 15:55). The Passion, as rich as it is, is not Jesus’ final statement. Even the angel at the tomb ispart of the conspiracy of surprise and joy: “Woman, why are you weeping?” (John 20:15). The angel knows the answer to the question but teases dramatically. (Indeed all modern European secular drama stems directly from this scene, the Quem quaeritis.)

Later Jesus withholds his identity from those who walked to Emmaus after the resurrection until “he was at table with them. And heir eyes were opened and they recognized him; and he vanished out of their sight” (Luke 24:30-31). Jesus humorously indulges Thomas the doubter: “Put your finger here and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side” (John 20:27). Thomas does not have to touch, but believes on the evidence of the familiar jesting Jesus.

The angels announced to the shepherds: “I bring you good news of great joy which will come to all the people” (Luke 2:10). Again and again the Gospels are punctuated with the crowds’ amazement, with rejoicing. It is difficult to imagine a healing or a feeding of the multitude without good spirits and laughter. Such events are not dreary, but exciting. Jesus is not lugubrious, but joyful, and joy-making. He purges the world of grim sickness, poverty and wickedness. He makes all things new.

Seen in the original perspective of the Gospels, Jesus laughed.

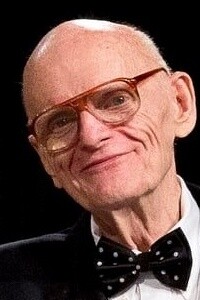

A prolific author and lifelong campaigner for the acceptance and inclusion of LGBT people by Christians and in the mainline church, Dr. Louie Crew Clay founded IntegrityUSA, a gay-acceptance group within the Episcopal Church, while teaching at Fort Valley State University in 1974. He married Ernest Clay in 1974 and then again in 2013, when marriage equality had become the law of the land. Known as Louie Crew for most of his life, he took his partner’s surname in his later years.